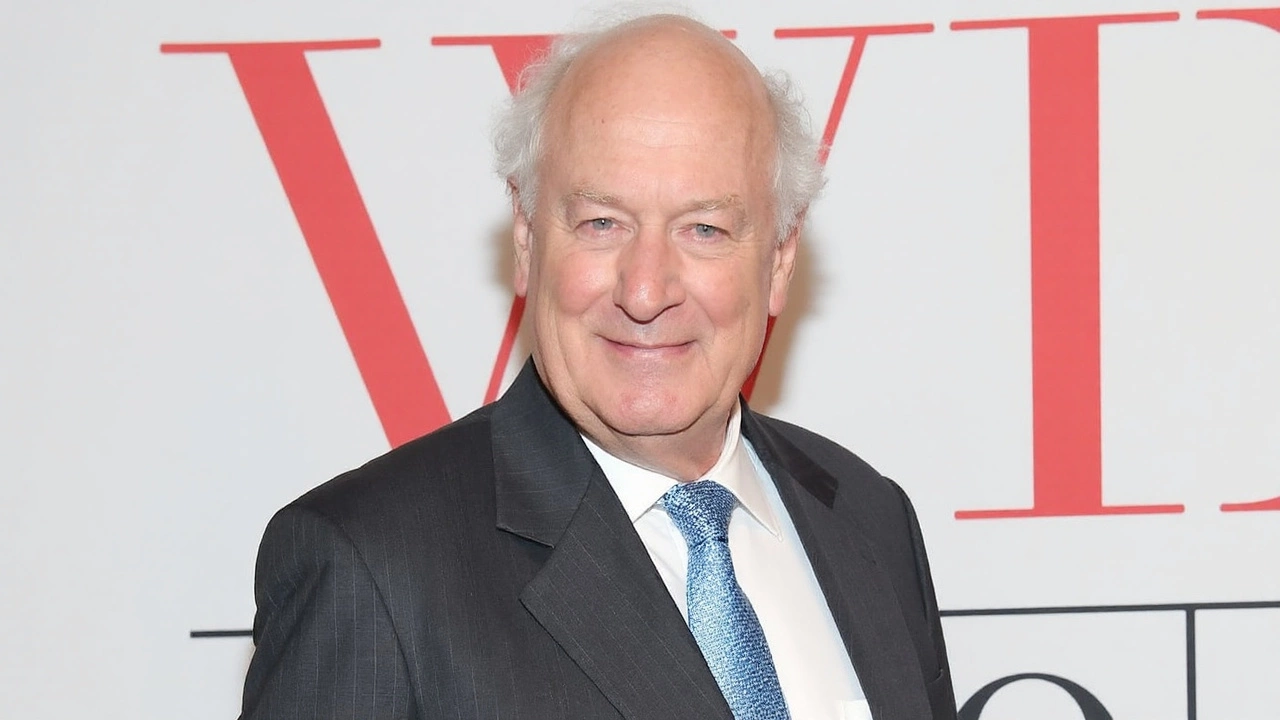

Jerry Adler didn’t step in front of a camera until his 60s. Then he became one of those faces you instantly knew—wry smile, dry delivery, pure New York. The actor, best known as Herman “Hesh” Rabkin on HBO’s The Sopranos and Howard Lyman on CBS’s The Good Wife, died in his sleep at his home in New York City on Saturday, August 23, 2025, according to his family. He was 96.

His representatives said he passed peacefully. By mid-morning, tributes from co-stars, writers, and longtime fans were circulating, the kind of grassroots memorial that follows performers who quietly elevate every scene they’re in. Adler’s career stretched from the golden age of Broadway to peak-TV dramas, and he treated both worlds like home.

A late-blooming screen career that stuck

Adler once joked that he was “too goofy-looking” to act. He didn’t buy the leading-man mold, and he didn’t try. The switch came in 1992 when casting director Donna Isaacson, a friend of his daughter, pressed him to audition for The Public Eye with Joe Pesci. He booked it, and the floodgates opened.

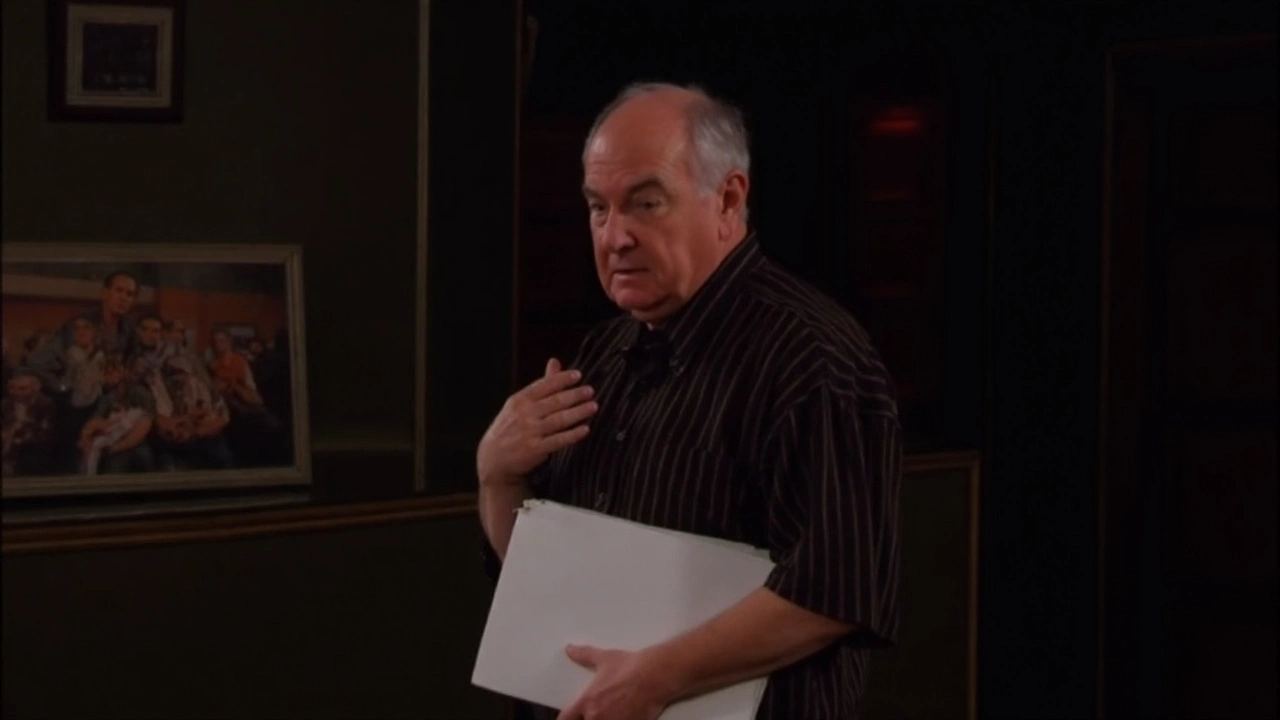

Film roles followed—small but sharp turns in Manhattan Murder Mystery, Prime, and In Her Shoes—where he used timing, not volume, to land a moment. Television soon became the main stage. He popped up as Mr. Wicker on Mad About You, brought a flinty authority to Fire Chief Sidney Feinberg on Rescue Me, and played Bob Saget’s dad on Raising Dad. If you needed a character with a lived-in New York edge, Adler was your guy.

Then came The Sopranos. As Hesh Rabkin, Tony Soprano’s longtime friend and music-business confidant, Adler gave the show a steady moral barometer outside the mafia hierarchy. He wasn’t a soldier. He wasn’t a capo. He was the older, savvy adviser who had been around longer than the rest—and knew when a bad idea was walking through the door. Across six seasons, he sharpened scenes with a raised eyebrow or a clipped line, grounding the chaos with cool pragmatism.

He found a second wind on The Good Wife as Howard Lyman, an old-school law partner who combined obliviousness and charm in equal measure. The role played to his sweet spot: a man shaped by another era, still learning how to operate in a new one. Adler revisited Lyman on the spin-off The Good Fight, delivering the same nimble humor that made him such a reliable presence.

Streaming audiences met him later as Moshe Pfefferman on Transparent, where he expanded a family portrait with a mix of tenderness and stubbornness. He turned up on Broad City as Saul Horowitz, and on Living with Yourself alongside Paul Rudd. It was never about racking up screen time. It was about making every minute count.

A life built in the wings of Broadway

Long before he ever faced a lens, Adler lived backstage. Born on February 4, 1929, in Brooklyn, he grew up in a theater household. His father, Philip Adler, managed productions for the storied Group Theatre and other Broadway shows. His cousin was Stella Adler, the influential acting teacher. So yes, he used to say, he was “a creature of nepotism”—his first job came through family while he was still in college.

What followed was decades of work that most audiences never see. Adler stage-managed, produced, and directed across 53 Broadway productions. He helped run the original 1956 Broadway run of My Fair Lady, a show that changed the musical landscape. If you’ve ever watched a tech rehearsal stretch into the night, or seen a stage crew race through a complex scene change, you’ve glimpsed the world Adler knew inside out: schedules, tempers, problem-solving, and the quiet pride of making chaos look smooth.

That training shaped the actor he became. Stage managers learn to read a room, anticipate what’s about to go wrong, and keep everyone moving. Adler carried that calm, organized presence into his on-screen work. He knew when to leave space for another actor. He knew when to cut a line in half and make it land harder. He knew when to say nothing at all.

His New York was never a cliche. It was a cadence, a shrug, the way he held a pause. On The Sopranos, it made Hesh feel like a man with history, not exposition. On The Good Wife, it turned Howard Lyman into more than a running gag; he was a familiar colleague who had to update his wiring while keeping his humanity. Adler wasn’t flashy. He was precise.

Colleagues admired that steadiness. Writers liked giving him layered beats because he never overplayed them. Directors trusted him to stick the landing on the first take. And fans—especially those who found him later through syndication and streaming—connected with the quiet intelligence he brought to men who had seen it all.

His path also pushed back on the idea that acting success must arrive early or not at all. Adler’s second act began around retirement age. It was proof that the industry still has room—if not always enough of it—for experience. His career sits alongside a small but meaningful group of performers who found their defining roles late in life, widening the frame for what working into your 70s and 80s can look like on American television.

The roles were varied, but the throughline was trust. When Adler entered a scene, you believed the world of the show a little more. Hesh’s advice to Tony, Howard’s misfires at the firm, Moshe’s complicated fatherhood—each felt rooted in something lived, not invented. That authenticity can’t be rushed. It comes from time, from listening, from the years he spent behind the curtain before he ever faced an audience.

Adler’s family confirmed his death with a brief statement and asked for privacy. Memorial details were not immediately available. Fans marked the news by sharing favorite clips—Hesh shutting down a bad plan with two words, Howard wandering into a meeting and derailing it with a smile—and by pointing to his Broadway decades as the foundation of it all.

He leaves behind a body of work that doesn’t need a highlight reel to make the case. It’s there in the background of classic theater, in the texture of prestige TV, and in the way he could turn a single reaction shot into a character’s whole point of view. That was the job as he understood it: do the work, make it true, move on to the next scene.

Arlen Fitzpatrick

My name is Arlen Fitzpatrick, and I am a sports enthusiast with a passion for soccer. I have spent years studying the intricacies of the game, both as a player and a coach. My expertise in sports has allowed me to analyze matches and predict outcomes with great accuracy. As a writer, I enjoy sharing my knowledge and love for soccer with others, providing insights and engaging stories about the beautiful game. My ultimate goal is to inspire and educate soccer fans, helping them to deepen their understanding and appreciation for the sport.

view all postsWrite a comment