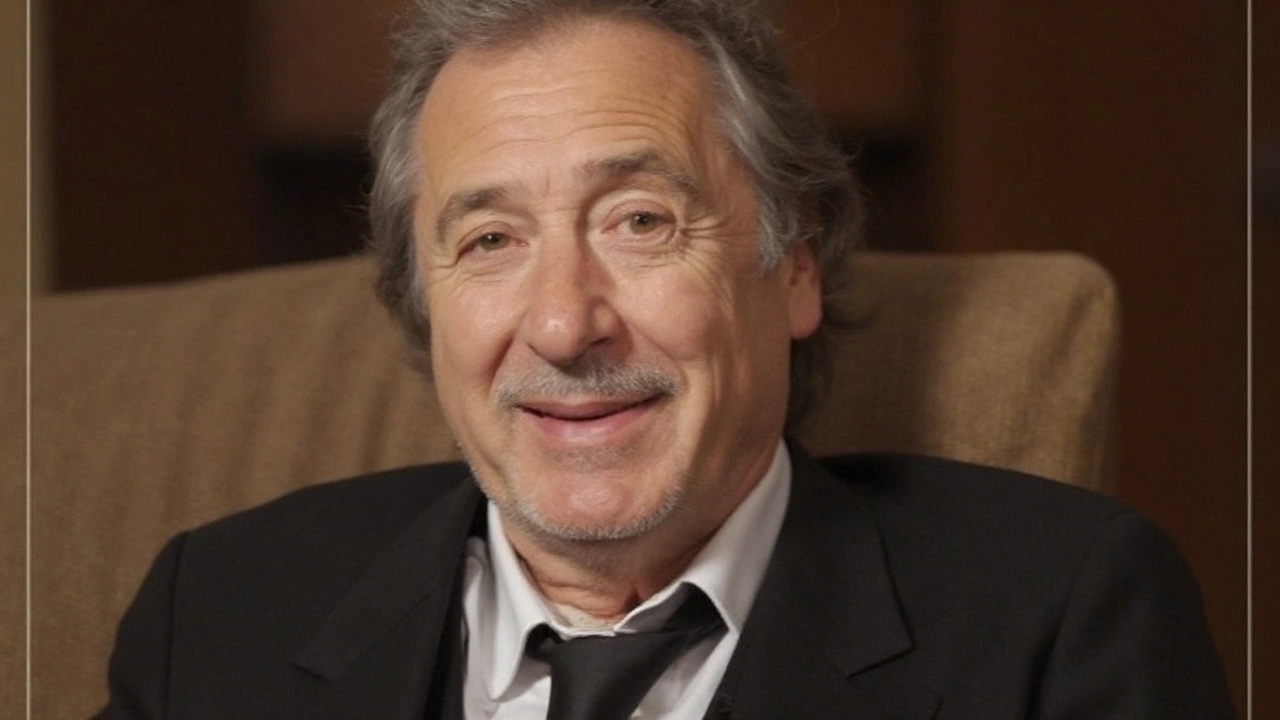

Pacino’s five — and what they say about the man behind the roles

Asked to name the films that define him, Al Pacino didn’t hesitate. He rattled off five titles: The Godfather, The Godfather Part II, Scarface, Serpico, and Looking for Richard. No pause. No hedging. He said he chose them "to show who I was." That quick answer tells you plenty. He wasn’t building a highlight reel for award shows. He was drawing a map of his identity as an artist.

The list spans five very different chapters: a street-level whistleblower, a reluctant mafia prince turned ruthless patriarch, an outsized 1980s antihero, and, finally, a self-directed search for Shakespeare on American streets. If you expected Scent of a Woman, the film that brought him his Oscar, or the cult-favorite Heat, you’re not alone. But Pacino wasn’t ranking peaks. He was circling the projects that shaped his voice, his method, and his curiosity about what acting can be.

Here’s how those five films line up, and why they matter to him:

- Serpico (1973, dir. Sidney Lumet): Pacino plays Frank Serpico, a New York cop who risks everything to expose corruption inside the department. It’s lean, restless, and anti-glamorous—pure ’70s urban realism. The commitment to detail is the point: the beard, the undercover work, the moral fatigue. This was Pacino proving he wasn’t just a sensation from The Godfather. He could carry a story on nerve and authenticity.

- The Godfather (1972, dir. Francis Ford Coppola): Michael Corleone starts as the clean-cut war hero who wants nothing to do with the family business. He ends the film colder and more calculating than anyone around him. Pacino’s performance is famous for what he withholds—quiet turns, long stares, a voice that drops as his power rises. It launched him and changed American film acting overnight.

- The Godfather Part II (1974, dir. Francis Ford Coppola): The sequel widens the canvas and darkens the soul. Michael is now the don, isolated at the top. Pacino leans into moral erosion without big speeches—just a slow hardening. The film won Best Picture. His Michael became a blueprint for the tragic antihero: brilliant, lonely, and unforgiving.

- Scarface (1983, dir. Brian De Palma): After the restraint of Michael, Pacino swerves into excess with Tony Montana, a Cuban refugee clawing his way up Miami’s drug world. Stylized, violent, and unapologetically operatic, the performance is a cultural weather system—imitated, quoted, debated. If the ’70s Pacino was about precision, this was about impact. He let the character get big without losing the character.

- Looking for Richard (1996, dir. Al Pacino): Pacino’s directing debut is a documentary about Shakespeare’s Richard III, but it’s really about the process of acting—table reads and street interviews, actors arguing about meaning, a star chasing a text until it surrenders something true. It’s intimate. It’s messy. It’s the bridge between his stage roots and his movie fame. This choice might be the most revealing of all: the craft comes first.

Taken together, these movies chart an arc from realism to myth, then back to the rehearsal room. They also remind you that Pacino is a theater creature at heart—Actors Studio, stage-honed instincts, a fascination with text. He didn’t pick the roles that made him richest or loudest. He picked the roles that taught him who he was.

That perspective lands differently when you remember the pace of his early run. Between 1972 and 1979, Pacino appeared in The Godfather, Scarecrow, Serpico, The Godfather Part II, Dog Day Afternoon, Bobby Deerfield, and …And Justice for All. In six years, he collected five Oscar nominations, multiple Golden Globe nods, and a BAFTA win. It felt like he was rewriting the job of a leading man—quiet one minute, combustible the next, never blinking on close-up.

That streak often overshadows the second half of his film career, which has been more uneven. He’s been open about practical choices—there were times he took work for money, and the scripts weren’t always great. But the later years aren’t a write-off. Not even close. He delivered acclaimed work on television—two Emmys, including a surge of life in Angels in America—and found a late-career cinema high with The Irishman, which earned him another Oscar nomination. The gears still turn.

Why these—and why not the obvious others?

Let’s deal with the two omissions fans bring up first. Scent of a Woman (1992) gave Pacino his long-awaited Oscar. The performance is huge by design—gravel in the voice, charm turned to 11, pain underneath. It’s an undeniable milestone. And Heat (1995) is the modern classic, the Pacino–De Niro face-off that launched a thousand think pieces. Yet neither made his personal five. That tells you his criteria weren’t trophies or memes. He was picking identity markers.

Serpico looks like the hinge. It’s the version of Pacino closest to documentary: street clothes, cramped rooms, fluorescent light. He’s chasing truth without polish, which lines up with his method roots and his attraction to moral tests. From there, the two Godfather films capture the control that made him a star—the slow burn, the ability to hold a shot without telegraphing emotion. Those films are where he learned the power of restraint.

Scarface is a different experiment. It let Pacino explore the theatrical side of screen acting—how to justify scale without tipping into parody. Tony Montana is big, but you can track every step: the hunger, the pride, the paranoia. It’s an actor testing range in public. The choice also acknowledges his impact on culture beyond awards season. Scarface lived on in posters, lyrics, and late-night dorm arguments. Few performances burrow into the zeitgeist like that.

Looking for Richard, though, is the curveball that explains all the others. Pacino has always returned to the stage—Shakespeare, the Greeks, David Mamet—when he wants to recharge. In the documentary, you see him wrestling the text to the ground, pulling meaning out of rhythm and subtext. He interviews people on sidewalks. He struggles, laughs, tries again. He’s not presenting a finished statue. He’s showing the workshop. That’s the point: for him, acting is a practice, not just a product.

If you zoom out, the five titles map a working philosophy:

- Start with reality you can touch (Serpico).

- Master silence and control (The Godfather, Part II).

- Test your limits in full view (Scarface).

- Return to the source and ask better questions (Looking for Richard).

The rest of his filmography circles those poles. Dog Day Afternoon sits near Serpico—raw nerves and ordinary desperation. Glengarry Glen Ross echoes the stage workshop energy, with language as a blunt instrument. Carlito’s Way feels like a mature reflection on crime and consequence after the blast radius of Scarface, quieter and more wounded. The Irishman brings the Godfather restraint back with age and regret baked in.

And then there’s the practical layer. For the last two decades, the market shifted, budgets moved to franchises, and adult dramas migrated to TV or streaming. Even legends have to thread the needle. Pacino has said there were stretches where he took roles for financial reasons, and you can see it in the credits: a mix of prestige projects and paycheck gigs. That’s not unique to him. It’s what the industry became.

Still, the through line holds. When the role asked him to interrogate power quietly, he thrived. When the material let him swing big with purpose, he went for it. When the work drifted toward routine, he looked for a stage or a text to wake it back up. Those five picks aren’t just his favorites. They’re his user manual.

There’s also a lesson in what the list refuses to do. It doesn’t chase consensus. It resists the neat story where the Oscar win equals the defining moment. Pacino picks the films that made him, not the ones that crowned him. For an actor who built a career on tension—between calm and explosion, order and chaos—that feels exactly right.

If you want the quick guide to Pacino, you can watch the five he named. You’ll get the quiet revolution (Godfather I and II), the moral grind (Serpico), the neon fever dream (Scarface), and the open notebook of a theater addict (Looking for Richard). But the real value is seeing how they connect. That’s the map he drew in seconds. That’s the career he was trying to show.

Arlen Fitzpatrick

My name is Arlen Fitzpatrick, and I am a sports enthusiast with a passion for soccer. I have spent years studying the intricacies of the game, both as a player and a coach. My expertise in sports has allowed me to analyze matches and predict outcomes with great accuracy. As a writer, I enjoy sharing my knowledge and love for soccer with others, providing insights and engaging stories about the beautiful game. My ultimate goal is to inspire and educate soccer fans, helping them to deepen their understanding and appreciation for the sport.

view all postsWrite a comment